No other form of art addresses so clearly the issues related to the process of formation of Brazil’s nation and culture as the visual arts. Our fine arts and architecture are strongly influenced by a foreigner outlook. To the point that “nothing is foreign to us, because everything is”, said the cinema critic Paulo Emilio Sales Gomes, who described not only the arts in particular, but our very own concept of “Brazilian culture”.

Even if we try to exclude the colonial Baroque period from this analysis, such period when creating original “Brazilian art” was not a concern, we note that since the early days of our modern arts, the eyes and the hands of the foreign “other” have influenced the constitution of the local subject, who is constantly seeking to find his own original culture – one that is autonomous and (self) critical. This scenario has changed since Debret’s reformulation of the European neoclassical concepts so that he could represent a world that was new to him.

The book edited by Maria Alice Milliet about the Hungarian artist naturalized Brazilian, Yolanda Mohalyi, brings this question to the fore once again. The process of “nationalization”, or, to put it more appropriately, the discussion about local particularities of our culture in the face of the challenges of the 21st century and Brazil’s modernism are central points of discussion in the life of the artist. Also, the book narrates the remarkable trajectory of the artist in the period between 1950 and 1970, and inspires the reader to reflect on the pertinence of the choices made by the artists of today. The book also covers the social art movement in the first half of the century and the compelling clash between abstract artists in the second half.

Yolanda arrived in Brazil in 1931, at the peak of the first stage of modernism, which was strongly influenced by the changes that the 1930 revolution was bringing about. Her educational background was typically European: as an artist’s daughter, she attended art schools. In Sao Paulo, she met numerous artists, immigrants as herself, who were seeking their places within an artistic movement that was firmly grounded in the values of a local, cosmopolitan and decadent aristocracy.

Quickly she let herself be carried away by the environment of ruptures and protest. Her first works were particularly influenced by the school of social expressionism, but not by socialist ideals. At that time she became closer to her mentor: Lasar Segall. With traces of Käthe Kollwitz’s criticism and much of Segall’s melancholy, her first engravings and paintings translate her attempts to adapt to and live in a place that was still unfamiliar to her. It is a nice coincidence that the launch of the book about Yolanda coincides with the publication of another book about her mentor. Segall Portátil is a bold and experimental project that proposes a presentation of the artist›s body of work by using braille, ink and sounds, inducing the reader to a sensorial search for meanings. The blind are enabled to see. Also, it is great news that the launch of this book coincides with the reopening of the Lasar Segall Museum.

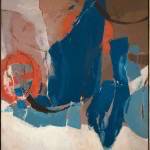

What to see and why are questions that have always been in the agenda of the discussions about Brazilian modern art – of which Yolanda took part of in her own way, conditions and choices. There is a lot to see and reflect about in the work of this humble artist, mainly about one of the main debates of the second stage of modernism: the one that challenged the advocates of geometric abstraction and the artists dedicated to the movement that became known as “tachisme” or informal (lyrical) abstractionism. In the well-crafted book and detailed research of Maria Alice Milliet, we follow the steps taken by Yolanda (leading her to participate in a number of biennales) and the informality (which largely corresponded to the taste of the emerging Brazilian middle class) with which she practiced a fairly different form of art when compared with her contemporaries (especially, the Japanese-Brazilian artists), with a very sophisticated palette of colours, shaping forms that, to a certain extent, never completely denied constructivism. Another foreign art worth mentioning, although a lot more bold and daring was the architect Lina Bo Bardi.

In the process of “Brazilianization” she dared to interfere vehemently in our modern architectural tradition. The books published by SESC uncover the artist, who brought together the ideals of a revolutionary, European collective imagination (the exemplary restoration of the old factory into the cultural space of SESC Pompeia aimed to establish a communal and politicized sociability, as if referring to the possibility of a “soviet” block in the middle of a working-class neighbourhood in Sao Paulo), and consistent research on Brazil, as if she were to continue what Mario de Andrade started. Other four books bring Lina well-known projects, which are sometimes explained by herself (who was also a great thinker of architecture and culture): MASP (with its open floor plan that works as civic and political square), Teatro Oficina’s space and its catwalk-like stage, Casa de Vidro (Glass House) and its dialect of transparency, nature and memory, Church Espírito Santo Cerrado, in Uberlândia (MG), communal project which, according to Lina herself, “was built by children, women and parents in the middle of the cerrado area, with very poor materials: handout gifts. (…) The most important aspect in the construction of Church of Espírito Santo was the possibility of a joint collaboration between the architect and labourers involved”.

The other book is an unpublished work. It is about Solar do Unhão Project in Salvador. In the project, the way that Lina conjugated her research about popular aspects of Brazil and modernist construction techniques in its libertarian philosophy are revealed through the simplicity of her intervention in a historical monument transformed into an original museum, i.e., her dream of MASP, which one day would come true. Our expats, such as Linda, Yolanda or Segall, will allow us to imagine what we are, and above all what we could have been, by being an eye opener to our own selves.

Deixe um comentário